Contributed Article

by Waltter Kulvik, Wesley Pydiamah, Sebastien Bonneau, Jukka-Pekka Joensuu, and James Hyde, Partners at Eversheds Sutherland

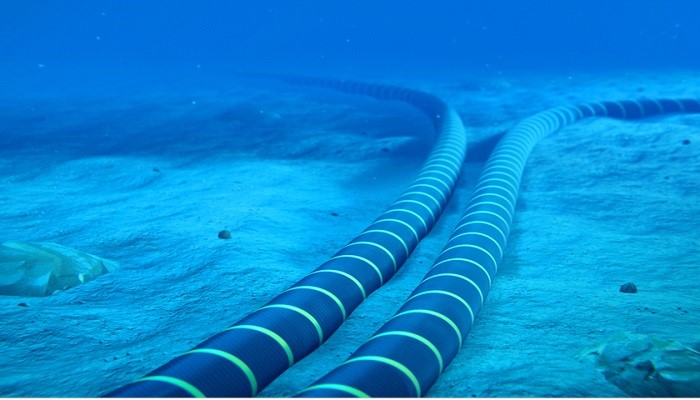

Subsea cable projects have traditionally followed similar structures, but recent market developments are prompting a re-evaluation.

Here are some key points:

Integrated projects

Demand is rising for partly or fully integrated projects that cover data centers, fibre connectivity, and – in some instances – power.

In the traditional model, each element operates independently with costs, financing, and returns being assessed separately. Depending on the circumstances, securing financing can become harder because of the multiplication of returns criteria to be met at the various levels, therefore placing the entire project at risk as each of its elements cannot economically and practically exist in isolation.

Integrated models simplify returns across the entire project. More specifically for sponsor-side investors, the complementing elements can be utilized to normalize returns across the project through the use of a single capex.

Development of such integrated projects will therefore require significant consideration on what the structuring will look like. A balance will need to be struck between optimising the structure from returns, construction, and future operational management standpoints on the one hand, and the lenders’ preferences on the other. This new approach will require parties to ensure that distinct lenders are comfortable in projects where both data centre and connectivity are financed (and not always by the same lenders).

Investment treaty protection

Selecting the jurisdiction for incorporating project vehicles has been traditionally largely tax-driven. While we expect this approach to continue to play an important role, the increased interest and scrutiny of governments on subsea cable security (and likely future related regulatory changes) are starting to highlight the importance of securing additional protections for foreign investments into cable systems. One way to achieve this is to structure the investments into the Host State through States (either of the investor’s nationality or third party States) that are parties to bilateral and multilateral investment treaties.

Multilateral and bilateral investment treaties grant foreign investors considerable rights and protections against expropriation (direct and indirect), nationalisation, discrimination, or unfair and inequitable treatment (including routine regulatory measures that may infringe such treatment) along with certain guarantees as to repatriation of profits without local impediments (such as e.g., approval from central banks to authorise foreign currency transfers).

These treaties offer investors a direct right of action against an infringing signatory state through international arbitration, which therefore avoids the need to have recourse to local courts. This is entirely separate to the right to make claims under the relevant commercial agreement and the forum provided therein. Investment treaties also have the merit of ensuring that protections remain in force even if local laws change, thus giving longer term certainty over the risks taken through a project.

Broadly speaking, to benefit from investment treaty protection, the investment needs to be structured through vehicles incorporated in a country that has the most advantageous investment treaty with the relevant jurisdiction(s). As such, in a number of cases, the structuring can easily sit alongside tax efficiency while affording significant additional protections for the project.

Financing challenges in subsea cable projects

Traditionally, subsea cable projects followed established financing models. However, the mix of parties involved, especially in consortiums, is evolving, and new challenges are arising due to the new variety of approaches.

Firstly, we have witnessed an increase in desire to use differing modes of finance across different segments of a cable (e.g. project finance, or advance sales). As a result, the scrutiny of the various parties involved over the projects has increased, significantly adding to the need to educate both lenders and customers as to the viability of the model and system delivery.

Secondly, on cable projects where certain sections will account for the majority of the revenue, questions have arisen as to whether a separation of the system or branches into distinct parts would considerably simplify financing and project execution. As parties look to build longer cables and finding alternative routings, we expect to see more issues of this sort which will further highlight the need for significant consideration of the structuring at the outset of the project.

Finally, we are seeing an emergence of ‘non-traditional’ consortiums with certain cable projects, in which parties have significantly differing backgrounds and interests in the system, including the manner in which they finance their participation (for example, consortiums covering a mixture of participating financing off balance sheet with parties needing to finance through debt, advance sales and/or government grants or support). Such conflicting needs and interest can naturally significantly impact both how the consortium operates, but also raise a need for parties to accept supporting to some degree demands of lenders or governments (including reporting obligations, undertakings and covenants) where they have not previously been required to do so.

As exposed above, the consequences of these new issues can have a significant impact on the development and construction of a new subsea cable system and should prompt the parties to anticipate such issues before they automatically apply traditional structures, and engage resources.

Join Eversheds Sutherland at Submarine Networks EMEA event next week! Get your ticket today